The Changing Energy Landscape of the Middle East

This column was published in World Oil Magazine: http://www.worldoil.com/magazine/2018/february-2018/columns/oil-gas-in-the-capitals#.Woj2SI1R8vw.twitter

FEBRUARY 2018 ///Vol 239 No. 2

Anas Alhajji

This is a time of evolution for governments and oil and gas companies in the Middle East region. Processes and policies are undergoing change, some of it quite significant. Here is a sampling of the more major items.

Saudi Arabia. Lifting energy subsidies without a major backlash from the public was an important event in Saudi history. The gradual phase-out of energy subsidies started on the first day of 2018. It raised prices for petroleum products and electricity. The increase was badly needed, not only to reduce the budget deficit, but also to improve energy efficiency and stop the smuggling of petroleum products to neighboring countries.

The Saudi Aramco IPO constitutes a sea change on how the government wants to transform its oil company into a world-class energy company, with major downstream operations around the world. The unknown facets of the Aramco IPO are the timing and location of the listing. The known intentions are to list during 2018 in New York, London and Hong Kong. While delays to 2019 are possible, the forthcoming visit of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman to the United States for a week in early March, after a trip to the UK, could expedite the decision on both the timing and place of the listing.

Focusing on renewable energy is another major change in the oil-oriented Kingdom. In 2017, Saudi Arabia issued tenders for 400 MW of wind power and 300 MW of solar power capacity. Officials plan to auction off 3.25 GW of solar power and 800 MW of wind power capacity during 2018. While the renewable capacity looks relatively small, it marks major changes in Saudi energy policy. All projects are expected to be online by 2021.

It is clear from the locations of the renewable projects that although the availability of solar and wind sources played a role, the cost of transporting oil to power plants in these areas has also played a significant role. For example, Saudi Arabia was shipping oil via tankers from the Arabian Gulf around the Arabian Peninsula, to ports on the Red Sea. Then, the oil was loaded into trucks that are driven on busy highways for hours to get to the power plant in the northwest of the country. The idea, here, is that the economics of these projects are overwhelmingly positive, once the cost of transporting oil is included.

Iran’s impact on the oil market is significant. The loss of Iranian oil exports during the 2011-2014 period contributed, along with the Arab Spring, to $100+ oil prices. The lifting of the sanctions—after reaching a deal with the Obama Administration regarding Iran’s nuclear program in 2015—increased Iran’s oil exports and contributed to the glut of 2015-2016. A few analysts attributed some of the increase in oil prices in recent months to the possibility that the Trump administration would end the nuclear deal and re-impose sanctions. It did not happen, as President Trump reauthorized the deal in January 2018, albeit only until May. But one thing was clear, once Iran reached its maximum production, growth came to a complete halt.

The Iranian government has not wasted any time, introducing a new oil contract, and running P.R. campaigns to attract foreign investment, and to market its oil. The new Iranian oil contract was introduced last year to avoid the problems of the old “buy back” contracts that started in 1995. There were numerous limitations on international oil companies (IOCs) that made many operators shy away from investing in Iran. Lifting these limits should help attract new companies, but the political risk remains high. French company Total was the top operator to enter Iran after lifting the sanctions. Iran aims to ramp its oil production through the development of South Pars phase 11 and Azadegan oil field. It remains to be seen whether Total can help Iran export its natural gas, and probably LNG, too.

Iran also brought several smaller oil fields online. It is investing heavily in shared fields along the Iraqi border. Iran also signed deals with Iraq to supply it with petroleum products and electricity, while also signing deals with Syria and Lebanon to supply them with electricity.

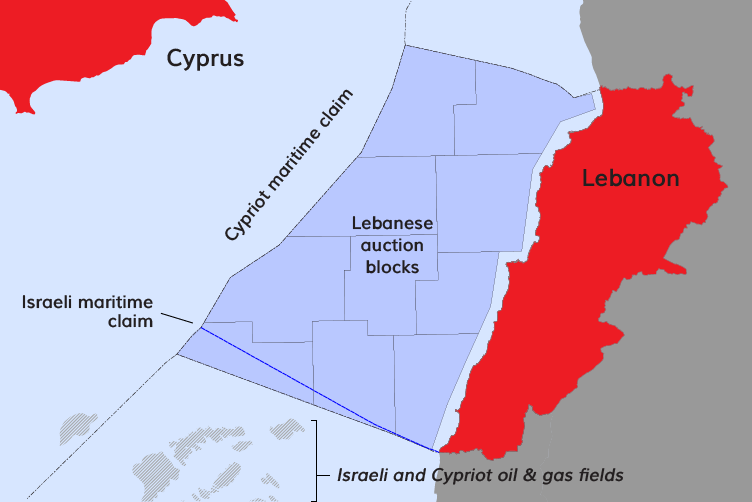

Lebanon. The Lebanese government issued licenses for an international consortium that consists of Total, Eni and Novatek, to explore and develop two of the country’s five blocks in the Mediterranean Sea. Lebanon, a country that depends heavily on energy imports, hopes to find oil or gas, or both, in sufficient quantities for domestic market and exports. Any oil or gas revenues will be welcomed by the cash-strapped government. Reality on the ground might not correspond with the high hopes and excitement, even among the Lebanese public. Any commercial hydrocarbons will be mostly natural gas, which is very expensive to produce, relative to today’s prices. As if this is not enough, Israel claimed that parts of Block 9 are within its waters. Experts predict increased tensions between the two countries, unless an agreement is reached.

Egypt. The development of what some say is the region’s largest natural gas field is expected to turn Egypt from a net importer to a net exporter. Before the collapse of the Mubarak regime. Egypt exported natural gas and LNG. After the collapse, if struggled to meet domestic demand, experienced major electricity shortages, and failed to meet its LNG export obligations.

Last December, Egypt started producing from Zohr, the largest natural gas field in the Mediterranean that is operated by Eni. Zohr has estimated reserves at 30 Tcf, with production reaching 1 Bcfgd in the middle of this year and 2.7 Bcfgd by the end of 2019. Consider how this major discovery will change the energy landscape in Egypt: it should eliminate electricity shortages, along with blackouts and brownouts, while halting all imports of LNG. Regionally, it killed a possible market for Israeli gas. ![]()

Comment